Sixty-fourth Issue! Cursed Blessings

As April unfolds, ushering in the promise of blossoming flowers and fresh beginnings, we eagerly present the sixty-fourth edition of the Flame Tree Fiction NEWSLETTER! Despite lingering traces of winter's chill, we've got two enchanting tales sure to ignite your imagination. A heartfelt appreciation goes out to all contributors for sharing their stories and bringing joy to our days. Here's to a month brimming with optimism, literary delights, and the hope of sunnier days ahead.

Congratulations to both winners of the April theme: Graham Robert Scott and Shana Ross!

The Strait of the Armilla by Graham Robert Scott – Amidst a naval pursuit and a navigational challenge, a mysterious boy with mystical abilities becomes the crew's only hope for survival. But his sacrifice weighs heavily on their conscience as they navigate treacherous waters...

Falling From Her Lips by Shana Ross – A woman named Alice grapples with a mysterious condition where objects fall out of her mouth when she speaks. Throughout her life, she navigates various challenges and experiences while discovering the origins of her condition.

This month's newsletter features:

- FLAME TREE PRESS: New titles coming this month!

- Gothic Fantasy: Latest releases

- CALL FOR SUBMISSIONS

- Original Fantasy Flash Fiction #1: The Strait of the Armilla by Graham Robert Scott

- Original Fantasy Flash Fiction #2: Falling From Her Lips by Shana Ross

- Next Month’s Flash Fiction Theme

FLAME TREE PRESS | April Title

We have two exciting new Flame Tree Press titles coming out in hardback, paperback and ebook.

Twenty years ago, a cult attempted to create their own god: the Lord of the Feast. The god was a horrible, misbegotten thing, however, and the cultists killed the creature before it could come into its full power. The cultists trapped the pieces of their god inside mystic nightstones then went their separate ways. Now Kate, one of the cultists’ children, seeks out her long-lost relatives, hoping to learn the truth of what really happened on that fateful night. Unknown to Kate, her cousin Ethan is following her, hoping she’ll lead him to the nightstones so that he might resurrect the Lord of the Feast – and this time, Ethan plans to do the job right.

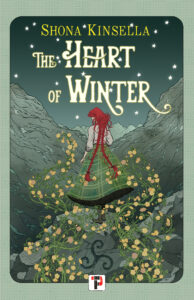

When Brigit is faced with a forced marriage to Aengus, god of Summer, she flees into the highlands in search of the Cailleach, the Queen of Winter. There, she hopes to learn how to live on her own terms, without the need for a man to speak for her, but can she persuade the Cailleach that she is worthy? Caught between two gods and finding an unlikely ally in the Fae witch, Nicnevin, Brigit will be tested to her limits and beyond.

Original Fantasy Story #1

The Strait of the Armilla

Graham Robert Scott

The Radamant attacked at dawn, guns strobing the fog and crack of cannon scattering seabirds.

Our enemy was faster on rough seas; our Armilla, more maneuverable. The fog, unpredictable coastal winds, and a reef enabled us to slip the barrage with reparable damage, and we inserted a league between ourselves and the privateer before the Radamant began gaining again.

I was the most ambitious of the junior officers that year. The captain tolerated my presence as he and the sailing master deliberated. Ministry charts predicted the shore would curve inland, and what appeared to be a bay would mouth into a strait to calm waters favorable to the Armilla. Ministry cartographers drew from the written accounts of missionaries deemed infallible, despite occasional evidence to the contrary. If the charts proved wrong, we could become trapped. The captain weighed options as the Armilla bulled through waves. Distant sails grew larger behind us. At last, the captain nodded curtly to the sailing master, who bellowed to riggers and the helmsman.

As the map predicted, the land bent into something like a bay. Yellow bluffs rose above the fog. Seals basked on salted rocks. Fog burned away under an indifferent sun. To either side, land first curled away, then grew closer. Behind, the Radamant drew closer too, this fact more felt than seen. If we halted, its swag-thirsty crew would be on us in a quarter of an hour.

The air cleared still more, unveiling an unfortunate truth.

The map was wrong.

No strait. No exit.

The captain glared at the sailing master, who squeezed the traitorous map in his fists.

From the land ahead rose the smoke of native fires. Silhouettes of Qagini natives along the crest. Woman with a basket. Man with a spear.

The Radamant appeared at the mouth of the bay.

The helmsman caught my eye and, perhaps anticipating my thoughts, shook his head.

I ignored him. “Bring the Nartik boy,” I called to a deckhand.

The captain arched a brow. I waited.

The boy soon stood before us. Slim and squat, stock of subjugated seamen and whalers. Flesh bearing diagrams of maker-priests. Every Nartik village keeps such a boy, but this one stole his binding stone and fled. He’d kept his nature hidden from the crew until one day he dropped the stone and I, a student of Nartik culture, picked it up and knew its worth. While I held it, the boy could neither leave me nor harm me.

I rolled the map out on the deck, kneeling on one end to keep it from furling.

“Make it true,” I said.

The boy studied the map, depicting a strait. The land, showing none.

He hesitated.

Making requires an effigy. I tapped the map.

“Look at the fires,” he said.

“This boy,” I explained, “knows runes of making. Two ports back, he wrote a woman for us on the stones of the shore. Then he added a rune and she sprang to life in a few hours.”

No one scoffed. To go to sea is to consort with miracles.

“To it, boy,” the captain said. “You know what they’ll do to us.”

The boy gestured at the shore. I looked but saw nothing, just smoke, fishing traps.

“Can you make a passage?” the captain urged.

“Yes, captain. But..."

“But what, damn you.”

“I can only make one thing at a time,” the boy said. “Don’t you see the people?”

The captain uncoiled a whip.

I opened my mouth and then shut it again.

The Nartik lad flinched to see the whip. Knew its sting. He looked at me, his soul in my pocket. I held out a knife. He took it and crouched beside the false map. He went still again.

“Boy,” the captain said.

Shaking, the boy carved a symbol on the land.

The coast ahead rumbled and the sea rushed in. The Armilla heaved forward.

The captain grinned. Crew cheered.

A Qagini fishing trap bobbed past.

A thatched roof spun in the water.

A child’s doll bumped the hull, spun idly away.

A rigger cried out and pointed.

My stomach knotted and my throat was tight.

With shivering shoulders and unmanly sobs, the boy pressed his head to the planks.

The Armilla followed the strait.

A deckhand pointed at the Radamant. “They aren’t following!”

“Would you?” whispered the helmsman.

“How long will this last?” the captain asked.

The Nartik boy sobbed. He cried out in his own tongue.

Distracted by unaccustomed feelings, I proved slow to translate.

I should have been stronger, the boy had said. I wish I were made of stone.

The boy touched his own flesh with the tip of my knife.

“No!” I cried, lurching toward him.

What I struck was unyielding, unforgiving, hard. I collapsed to the planks, chest and arms bruised. No longer moving, the Nartik boy gleamed like alabaster under the midday sun.

Hours later, the land rose. Treetops wagged beneath the surface, then tickled the hull, and the ship shuddered. The land rose until our passage found itself on a slope and the water below us raged forward, carrying us with a great rush into the sea on the other side.

We drifted on deeper and more natural water. Behind us, the land continued rising until we could no longer make out the way we came.

“He did it,” the sailing master said.

I touched the boy’s cool shoulder.

The captain stepped before the Nartik boy. Studied his unblinking eyes.

A moment passed.

The captain said, “Throw it over.”

“Sir?” I asked.

“Get rid of it.”

I gathered four men, and we dropped him into the sea.

I watched the water swirl where he entered and then forget his passage.

I reached into my pocket. Felt the stone there and warred within. Imagined skipping it to his resting spot. Ultimately, I kept it. I tell the others he boarded our ship for a reason. I assure them the stone will know where to stop.

Graham Robert Scott grew up in California, resides in Denton, Texas, owns neither surfboard nor cowboy hat. His speculative fiction has appeared in Nature, Pulp Literature, Barrelhouse, and others. When he isn’t telling tales, he teaches English and works in accreditation at Texas Woman's University. In more unproductive moments, he lurks on social media sites like Bluesky (@graythebruce.bsky.social) and the site formerly known as Twitter (@graythebruce). He maintains a list of his short stories on an admittedly lazy blog located at https://hemicyon.wordpress.com/creative-works/.

Original Fantasy Story #2

Falling From Her Lips

Shana Ross

She remembered the visits to the doctors; she didn’t remember the curse starting. But this was her condition: when Alice opened her mouth, something would fall out with every sound she made.

When she was a kid, nothing could slow her down. She chattered and argued and gossiped and opined and laughed. She was oblivious to the stares as things piled up – rats and roses and butterflies. Bouncy balls, once. Ice cream in scoops with no cones. Wrens, in a flock.

She got used to the reactions of teachers. Some thought she was brilliant and collected her droppings. Others didn’t bother to hide their annoyance, although who knows exactly what they resented – that she felt entitled to speak as much as anyone else in class? That she spoke up uninvited if they refused to call on her? That she had the adoring attention of her classmates, with or without the blessing of their authority?

In college, she tried something new. She wondered what it might be like to be ordinary. Or at least not inescapably odd. She developed an alluring smile and a brow that could arch fifty different ways. She cultivated an air of mystery.

Her silence made her extremely popular, at first. But she quickly saw that for what it was. She spoke up and spoke out. Worth it, she lied to herself, a pariah on campus.

Josh, oh, that idiot, had seen all her righteous opinions erupting on the lawn and found it brave. He asked her out. Again and again.

His idea of a date was to take her to the overlook and talk late into the evening. At first she whispered marshmallows, pear blossoms, other bland sweets. Then brackish water, dark lake weeds, sewing needles.

He stayed, listened, held her closer and closer.

She did not hold back. He knew what he was getting into. He did his best to be as honest.

* * *

After college, a blur of striving. She was supposed to silently execute the big ideas of big and bigger men. She was supposed to absorb the unspoken rules without asking questions. She tried.

She worked so hard that she was surprised, one night, to arrive at her small apartment and find it…empty. Evidence of her new and persistent silence.

When was the last time she had talked to Josh?

She called, asked him to move in. Bright, shiny pennies trickled then poured, accounting her fears and loneliness. The clinks sounded cheerful from the other end of the phone, like new beginnings.

She started speaking up in meetings, impossible to ignore, her comments accumulating on the conference table. Material and hard-edged questions, the occasional living, squirming insight. That was the beginning of the end, though it took the legal team ages to figure out how to fire her. She was not sad to be let go.

She took an accounting job. It paid well, if not absurdly. If she said little, it was probably because there wasn’t all that much to say.

She began talking in her sleep and waking up with small scatterings of freshly turned dirt on her pillow. Red clay. White clay. She got a mouthguard instead of a therapist. Her dentist approved. She had been grinding her teeth for a long time.

Josh kept taking her on walks. “I wonder,” he said, “how many other women are out there like you. Exceptional. Living extraordinary lives, and the world hides them instead of celebrates them.”

“I love you,” she said. “Let’s get married.”

* * *

They built a life, and it was good. They moved out of the city. They met new people. They hit a groove where Alice trusted Josh to do most of the talking. It was easier. After all, they were a team, and she knew she was a full partner.

They got pregnant. Alice assumed she would go back to work after the baby, but she yelped out a sprig of tarragon with the pain of every latch, nothing working quite right. Exhaustion stretched out as far as she could see and she didn’t see the point in going back to a job that was fine, with people she liked well enough. They didn’t need the money.

She stayed at home.

The girls, babies then squishy toddlers, loved her singing, loved to guess what would fall from her lips. She would talk to them constantly, to give them words, and the house overflowed with the remnants of her love.

But children grow quickly, and her condition became inconvenient again, then embarrassing. She was certain she was choosing silence. She stopped noticing that she was silent.

Everything unsaid gnawed at what it could reach. Her fashion sense. Her vast stores of odd facts, useful only for pub trivia. The threads of her oldest friendships. Her ambition.

* * *

One night, the memory arrived, like a body unsticking itself from the bottom of a peat bog.

Her childhood sleepaway camp. A lady in the woods asking for water, flowers tucked into her greying hair. Alice was supposed to be heading to the craft cabin. Instead she was going to…not do that. Her grand plan was to sit in the woods, alone, while everyone else stuck to the schedule. It seemed like a tremendous rebellion at the time.

“No,” said young Alice, “I’m going somewhere.”

“Are you really?” asked the old woman.

“Why wouldn’t I be?” said Alice.

“Well, if you sound certain,” said the woman, “you must be.”

Alice scurried off. When she looked back over her shoulder, the woman was gone.

* * *

“Well, well, well,” said Alice in the dark of her bedroom, filling it with a cloud of fireflies. She sat for a long time, covers askew, watching them blink.

She snuck down to make coffee.

“You’re up early,” yawned Josh as he padded into the kitchen.

“I found myself awake,” said Alice, fishing a piece of parchment out of her teeth. In a clean, looping script, someone had written: About time. Go get ’em.

Shana Ross is a new transplant to Edmonton, Alberta and Treaty Six Territory. Qui transtulit sustinet. Her work has appeared in Radon Journal, Swamp Ape Review, The Dread Machine, Haven Spec and more. She serves as an editor for Luna Station Quarterly and a critic for Pencilhouse. She’s been feeding the magpies in her backyard for about a year, but friendship (and a devoted corvid squad) takes more time, and/or more peanuts, it seems.

Sign up for our fiction newsletter

Sign up for our fiction newsletter